Stay ahead with precise, independent journalism of APAC's insurance markets.

Experience 7 days of full access to premium insights

Already a member?

Login here

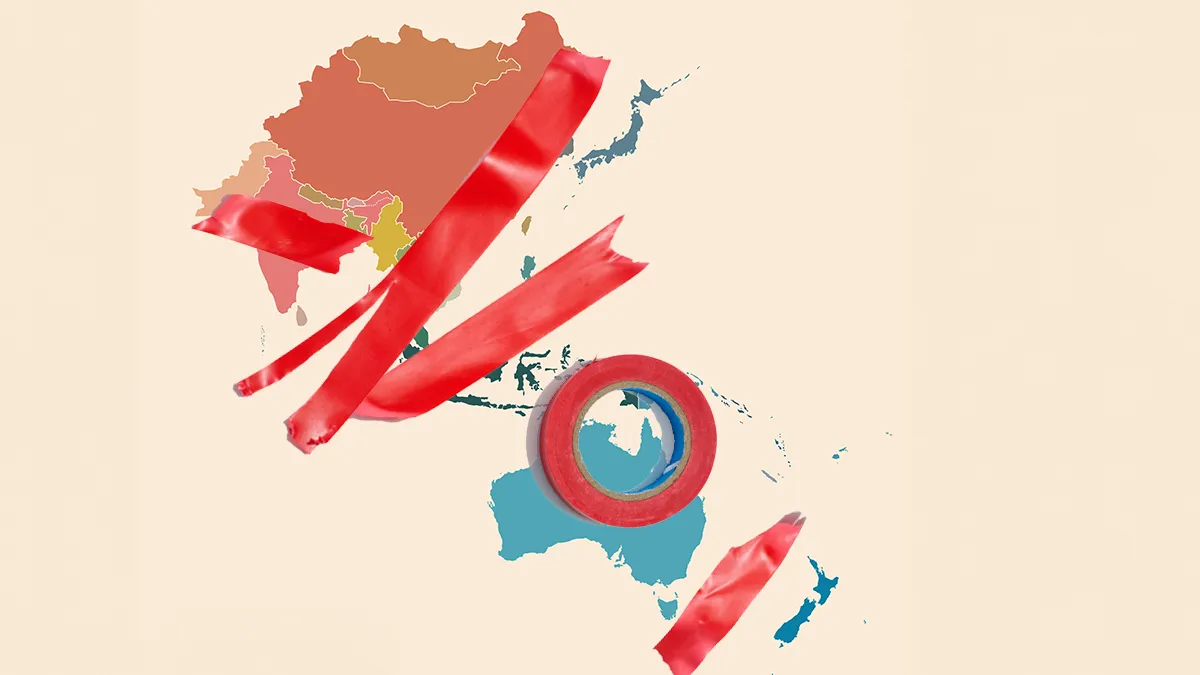

Emerging risks | Growth Opportunities | APAC Insurance

Share

Stay ahead with precise, independent journalism of APAC's insurance markets.

Experience 7 days of full access to premium insights

Already a member?

Login here